Iraq: Why Are Kurdish Women Dying of Burns?

Sept. 18, 2007 – The doctor knows, just from glancing at the burns, that someone is lying to him. Srood Tawfiq, a reconstructive surgeon at Sulaimaniya Hospital in Iraq’s northern Kurdish region, buttons his white lab coat and steps into the burn unit. “Busy day yesterday,” he says, pulling back a curtain to reveal a sleeping 16-year-old girl with kerosene burns over 90 percent of her body. The mother of the young woman, hovering over the hospital bed, tells Tawfiq that her daughter slipped and scalded herself while carrying a portable stove. The doctor listens sympathetically. But later, out of the woman’s earshot, he explains that he doubts the mother’s explanation. If it were really an accident, he whispers, “you don’t get this degree of burn.” Outside the hospital room he pulls off his hygienic mask and shakes his head. “We never tell them that they’re going to die,” he says quietly.

Kurdistan has long been considered the one consistently safe and relatively prosperous region of Iraq. So why, in increasing numbers, are the territory’s young women showing up at local hospitals dying of suspicious burns? According to the Women’s Union of Kurdistan, there were 95 such cases in the first six months of 2007, up 15 percent since last year. A December 2006 report from the Asuda women’s rights group in Sulaimaniya says that the “phenomenon is increasing at an alarming rate.” Ninety-five percent of the victims are under 30, and roughly half are between 16 and 21. On the day before I stopped by the emergency hospital in Sulaimaniya, six young women were admitted with major burns, three of them telling suspicious stories. When I called Zryan Yones, the Kurdish health minister, he said that the trend among young women is more disturbing than a recent outbreak of cholera. He provided a startling statistic: since August 10, Kurdistan had had nine deaths from its cholera epidemic; in the same period, there were 25 young women dead of burns. “I have one young girl lying in our morgues every single day,” he told me.

So what’s going on? Most of the survivors tell doctors that the burns resulted from a “cooking accident.” But surgeons told me they can tell that the vast majority are not telling the truth. Kerosene, the fuel used to cook here, is not particularly volatile; if a woman comes in with burns over the majority of her body, it is likely intentional. Women’s rights advocates in Sulaimaniya believe that the majority of the burn cases are suicide attempts; the remainder are suspected to be honor killings or other murders disguised as accidents or suicide. (“Cooking accident” has long been a euphemism for dowry killing in India.) Doctors told me that it’s virtually impossible to distinguish between murder and suicide based on the burns and the women’s stories. Still, anecdotal evidence suggests that the trend may be aggravated by a copycat effect among Kurdistan’s teenagers. One 20-year-old woman, Heshw Mohammad, who briefly considered burning herself after her father killed her boyfriend two years ago, told me that self-immolation has become a sort of fashion among teenage Kurdish women. “They imitate each other,” she says.

What’s the motive—and why fire? Doctors, rights advocates, and young women I spoke to described a collision of local tradition with modern technology and the fallout from the Iraq war. Death by immolation has a long history among ethnic Kurds. When someone is angry here, a popular interjection is “I’m going to burn myself!” Locals I talked to attributed the fire obsession to various local cultural sources. The Zoroastrian religion uses fire as a prominent symbol. The Kurdish new year, called “Nawroz,” commemorates the day a folk hero named Kawa killed a tyrant named Zohak and then set a fire on a mountaintop to tell his followers; Kurds celebrate the day by burning tires and with other pyrotechnic displays. “Burning, traditionally, has been the way to die among the Kurdish people,” says Yones, the health minister.

Most of the burn cases in Kurdistan—whether suicides or honor killings—revolve around love and dating. Heshw Mohammad’s case is typical. When she was 18 she fell in love with a local boy, and the two started seeing each other, which is generally frowned on in Kurdistan’s traditional society. They communicated secretly by text message on their mobile phones to arrange meetings. But her father had other ideas about his daughter’s future; he had already promised her to one of his friends. When Heshw’s boyfriend asked her father to let the girl marry him, her father gunned the boy down with an AK-47, she says. She later attempted suicide by overdosing on medication, but she acknowledges that burning herself “crossed my mind.” After the killing, her boyfriend’s father took her to a women’s shelter in Sulaimaniya, where she now says she sleeps late and spends her time watching South Korean soap operas on satellite TV. “I have no plans for the future,” she told me. “I’m quite sure I will be killed in the end.”

Rights advocates explain that the introduction in the past several years of inexpensive mobile phones and e-mail to Kurdistan have made dating and casual sex easier, even as the old patriarchal social structures remain in place. “The explosion of technology has alienated people from themselves,” says Samera Mohammad of the Rassan women’s rights center in Sulaimaniya. She says that a disturbing number of the suicides involve boys who take pictures of their girlfriends with their camera phones and then show their friends. But rights advocates say that even something as simple as bad grades can be a motive for self-immolation.

The Iraq war only made things worse. Refugees from Iraq’s cities, some of whom have turned to prostitution to earn a living, have flocked to Kurdistan from elsewhere in the country, challenging rural sexual mores and the religious beliefs of the mostly Sunni Muslim Kurds. Kurdistan’s lakeside resorts are said to be a popular destination for sex workers in search of easy income. “With the arrival of prostitutes, men have become more suspicious of their daughters,” says Paiman Izzedine of the Women’s Union of Kurdistan. Economic factors have also aggravated the problem, according to locals. The price of kerosene, for example, has tripled since the war began, its price swinging wildly, black-market dealers told me. That means households now stockpile the fuel for the winter in large quantities when they can get it cheap—providing young women with inspiration and an easy weapon.

For now, the suicides are a phenomenon that is seldom discussed openly in Kurdistan. Srood Tawfiq, the surgeon at Sulaimaniya’s burn center, says he has seen only five or six cases in which the patients admitted to a suicide attempt. Rights advocates told me that they’re beginning to hold conferences in local villages to educate teachers and other community leaders about the problem. Yet even Tawfiq acknowledges that he doesn’t press his patients too hard about their real motivations. “We don’t insist on the cause,” he told me, as we talked outside the burn unit. “We just ask once; we don’t push it.” Even in relatively peaceful Kurdistan, sometimes the truth is too merciless to speak.

|

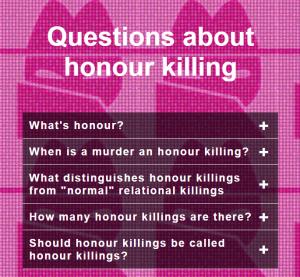

What is an honour killing? |

|

An honour killing is a murder in the name of honour. If a brother murders his sister to restore family honour, it is an honour killing. According to activists, the most common reasons for honour killings are as the victim:

Human rights activists believe that 100,000 honour killings are carried out every year, most of which are not reported to the authorities and some are even deliberately covered up by the authorities themselves, for example because the perpetrators are good friends with local policemen, officials or politicians. Violence against girls and women remains a serious problem in Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Serbia and Turkey. |

Latest posts

-

Europees Rapport: Nederlandse politie faalt bij afhandeling eerwraak

-

Echtgenoot (42) aangehouden na dood 33-jarige vrouw in Zaltbommel

-

Eerwraak in Kabul, Afghanistan? De verdwijning en dood van de 17-jarige Farkhunda

-

Doofpot brandmoord Narges Achikzei: 240 getuigenissen ontmaskeren jarenlange wegkijkpraktijken Inspectie Justitie en Veiligheid

-

Verdwijning van Yildiz Kayali uit Zevenaar leidt tot zware straf voor partner

-

Eerwraak in Eskilstuna, Zweden: Abier vermoord vanwege haar wens te scheiden

-

Eermoord in Mailsi, Pakistan: schoonmoeder in brand gestoken na weigering van verzoening

-

Eermoord in Nahavand, Iran: 26-jarige atlete Raheleh Siyavoshi vermoord door haar echtgenoot

-

Vermoedelijke eermoord op jonge ingenieur in India

-

Eerwraak in Uttar Pradesh, India: 17-jarig meisje doodgeschoten door vader en broer