Kurds Tackle ‘Honor Killings’ of Women

SULAIMANIYAH, Iraq (AP) – She is 18, unmarried and eight months pregnant. She hates it when the baby shifts and kicks in her womb.

“I don’t hate the child,” she said. “But the movements keep reminding me of my past.”

After she gives birth in secrecy, she will give up her child for what she describes as her family’s honor. Then she will travel home to the Kurdish area of northwestern Iran to find a husband who knows nothing of her story.

Secrecy is essential, because in her world, a child out of wedlock can lead to an “honor killing”—her murder by a relative to protect her family’s honor. So she is known in this city only as Banaz, a nickname.

Tarza, 22, also uses a nickname. She sits on a sofa and weeps, wiping her nose with her leopard print head scarf. She gave birth out of wedlock in 2003, a few months after the U.S.-led invasion that ousted Saddam Hussein, and says her male-dominated clan wanted to kill her for sullying their reputation.

Tarza, an Iraqi Kurd, said the threats persist. She lives alone with help from a women’s center that arranged for an Iranian family in Sweden to adopt her child.

“I don’t want to see the child,” Tarza said, her face taut.

Honor killings, driven by the view that a family’s honor is paramount, are an ancient tradition associated with Kurdish regions of Iraq, Iran and Turkey as well as tribal areas in Pakistan and some Arab societies.

While the rest of Iraq is preoccupied with the violence that has followed the U.S. invasion of 2003, the more peaceful Kurdish enclave of the country stands out in its attitude to honor killings. Here, officials who long ignored this explosive and deeply personal issue of family pride are seeking to curb the murders.

Civic activists welcome the regional government’s condemnations of the custom and warnings of tough penalties, but say much more education and law enforcement is needed.

This year, the British government arranged for a delegation of Iraqi Kurds to travel to Pakistan to talk with officials there about their experience in combating the brutal tradition.

Some reports cite several hundred honor killings or related suicides a year in Iraqi Kurdistan, which has more than 4 million people. But there are no reliable statistics for a crime that is difficult to prove without effective law enforcement and the cooperation of tribal communities.

The number of women who committed suicide by setting themselves on fire increased from 36 in 2005 to 133 in 2006, while the murder of women rose from four to 17, according to a report by Kurdistan’s human rights ministry.

The report makes no specific reference to honor killing. But one theory circulating in Kurdistan is that because penalties for murder have been stiffened, more men are resorting to coercing women into killing themselves.

In 2002, Kurdistan’s parliament revoked Iraqi laws that allowed defendants to be cleared or treated leniently in the case of an honor killing. These laws, it is believed, were instituted by Saddam Hussein to curry favor with traditionalists.

“Killing under the pretext of protecting honor is murder,” the region’s prime minister, Nechirvan Barzani, said in July.

Another reason for the changing attitude could be the Western influences that have taken root here since the enclave—the Iraqi part of a historical Kurdish homeland stretching from eastern Turkey to western Iran—became a Western protectorate following the 1991 Gulf War.

“Western culture is growing here and is in contradiction with the old tradition that honor is something sacred,” said Runak Faraj, head of the Rewan women’s center in Sulaimaniyah, one of Iraqi Kurdistan’s two main cities.

She said the values of the young are clashing with tradition, which maintains that pregnancy before marriage or an extramarital affair can be grounds for killing a woman, or pressuring her to commit suicide. Even the hint of a teenage romance lacking elders’ approval can mean death.

Women in Iranian Kurdistan appear freer than in Iraq, able to go out unchaperoned with boyfriends, which suggests Banaz will have an easier time than the Iraqi, Tarza.

Banaz got pregnant in Iran after her boyfriend invited her to a party, and five months later she told one of her four sisters. They asked doctors to abort Banaz’s child, but were refused.

Banaz knew the stigma would stain her two married sisters, and make it hard for her unmarried sisters to find husbands.

She tried to commit suicide by throwing herself from the top floor of her home, but a sister restrained her. She overdosed on pills but vomited them up. She considered dousing herself in gasoline.

“Burning was the final option. I was too scared to do it,” Banaz said in an interview at the Rewan center. She spoke softly, but with confidence, and smiled easily.

Her father found out and sent her to Iraqi Kurdistan, ostensibly on a study trip, but the doctor she consulted in Sulaimaniyah refused to perform an abortion.

She found refuge in Faraj’s center, and will give birth by Caesarean section. Faraj will search for an adoptive family.

Banaz’s family calls her twice a month.

“I think more rationally than emotionally because it’s only one child. My home, my family, my history is in Iran. I have decided not to think about the child anymore,” Banaz said. “I have to show that nothing happened. I have to change what’s in my mind.”

Many women turn up at hospitals with severe burns that doctors suspect are the result of suicide attempts linked to family honor, possibly coerced by male relatives who don’t want to kill the women and face prosecution for murder.

“Before coming to the hospital, they will agree on a story: ‘While she was cooking, that happened. While she was in the bath, that happened,’” said Dr. Ahmed Amin, a medical director of Heartland Alliance, a human rights group based in Chicago.

Cell phones are also part of the problem. According to a columnist in Soma Digest, an English-language newspaper in Kurdistan, there are cases of men dialing randomly until they reach a woman, whom they then harass with more calls or text messages. Saved in the phone’s memory, these raunchy calls can endanger the woman’s life if a male relative discovers them and believes they are from a boyfriend, the newspaper said.

Tarza, the Iraqi Kurd, has had repeated exposure to the world of honor killings.

Last year, she said, one of her two sisters asked for a divorce, and was later found shot to death. The husband was detained for 15 days and released.

Tarza has no contact with her other sister, who was also under threat of death because she became pregnant by a boyfriend. With help from activists, she married another man, severing contact with her family for her own safety.

Her father was killed in a land mine explosion when she was 3 months old. Her mother remarried, but it is too dangerous for Tarza to meet her.

“If somebody learns about it, we could both be killed,” she said. She looked at the floor, her expression hard, clasped her hands and ground them together.

|

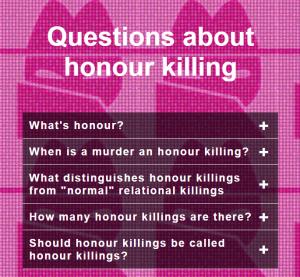

What is an honour killing? |

|

An honour killing is a murder in the name of honour. If a brother murders his sister to restore family honour, it is an honour killing. According to activists, the most common reasons for honour killings are as the victim:

Human rights activists believe that 100,000 honour killings are carried out every year, most of which are not reported to the authorities and some are even deliberately covered up by the authorities themselves, for example because the perpetrators are good friends with local policemen, officials or politicians. Violence against girls and women remains a serious problem in Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Serbia and Turkey. |

Latest posts

-

Echtgenoot (42) aangehouden na dood 33-jarige vrouw in Zaltbommel

-

Eerwraak in Kabul, Afghanistan? De verdwijning en dood van de 17-jarige Farkhunda

-

Doofpot brandmoord Narges Achikzei: 240 getuigenissen ontmaskeren jarenlange wegkijkpraktijken Inspectie Justitie en Veiligheid

-

Verdwijning van Yildiz Kayali uit Zevenaar leidt tot zware straf voor partner

-

Eerwraak in Eskilstuna, Zweden: Abier vermoord vanwege haar wens te scheiden

-

Eermoord in Mailsi, Pakistan: schoonmoeder in brand gestoken na weigering van verzoening

-

Eermoord in Nahavand, Iran: 26-jarige atlete Raheleh Siyavoshi vermoord door haar echtgenoot

-

Vermoedelijke eermoord op jonge ingenieur in India

-

Eerwraak in Uttar Pradesh, India: 17-jarig meisje doodgeschoten door vader en broer

-

Schietpartij in Sneek: Daniel el Makrini (32) schiet zwangere ex-vriendin neer en pleegt zelfmoord